The history of skateboarding – from a street skater’s point of view

Born in the streets, pushed to the parks

Skateboarding is a creation of the modern urban city. Just like skiing is because of the snow, surfing because of the ocean waves and the giraffe because of the savanna landscape, there would probably not be any skateboarding without the emergence of smooth paved man-made ground. Skateboarding is tied to the city forever and wherever skateboarding may venture, it never really leaves its naturally given home in the streets.

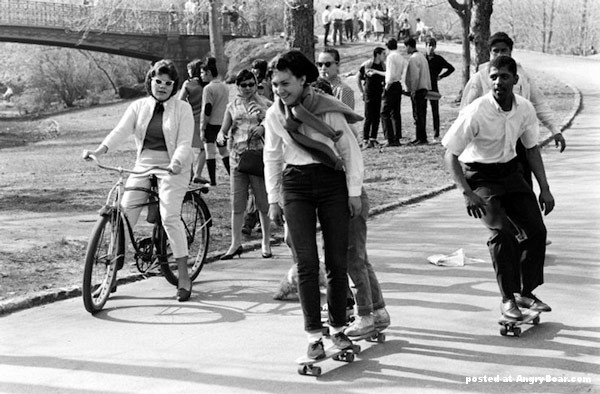

Some of the first photographs of skateboarding are shot in NYC in the 1950’s. Young people cruising on rickety boards on asphalt park walkways. Fascination was strong but equipment poor. Wheels were made of harsh metal or ceramic materials and ball bearings were not sufficiently developed hence a seemingly early death for the new urban hobby.

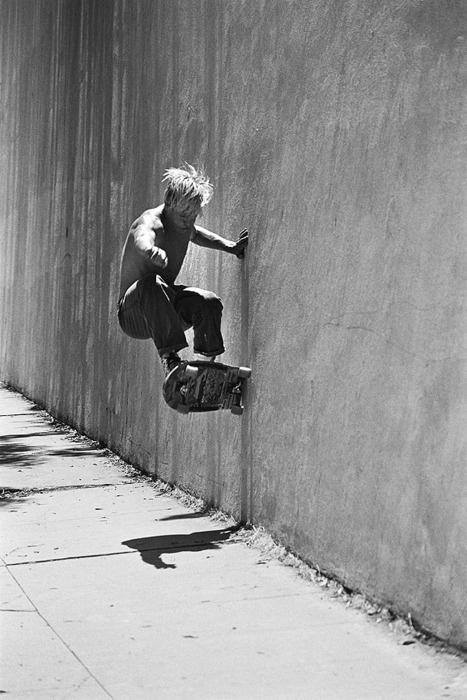

The second coming of skateboarding in the 1970’s is solely linked to the emergence of urethane wheels. This is the same petrol based material that wheels are made of to this day and the fast grippy stuff made skateboarding go places no one could have ever imagined, even up the vertical walls of empty swimming pools.

So equipment picked up and skateboarding bloomed. But something went wrong again. Society panicked over the unruly toy. Here in Sweden, skateboarding was condemned as a life threatening and morally harmful activity and skateboarding in public places was outlawed “on arrival” in Stockholm in 1976.

Also, skateboarding’s powers of adaption was not yet realized and the notion that skateboarding needed specially designed terrain became prevailing. Loads of money was invested in the building of ramp-oriented skateparks that soon closed or got demolished due to poor design and a general slowing in the popularity of skateboarding.

Early skateboarding

Vert vs. Flat

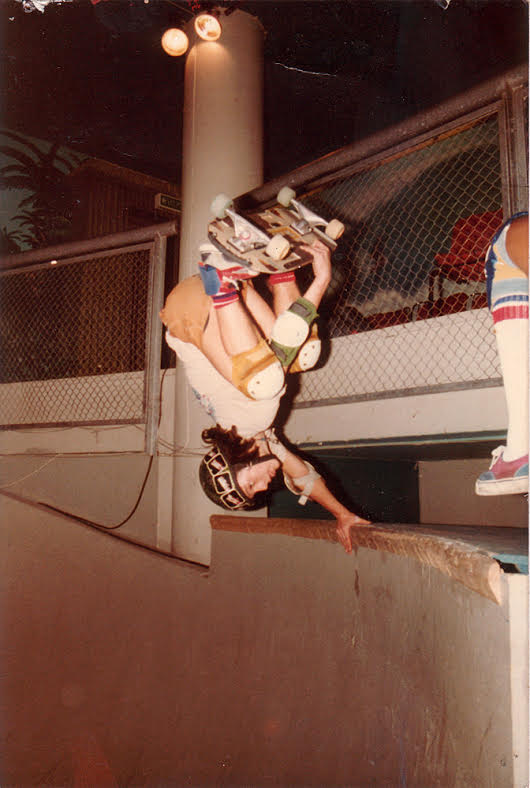

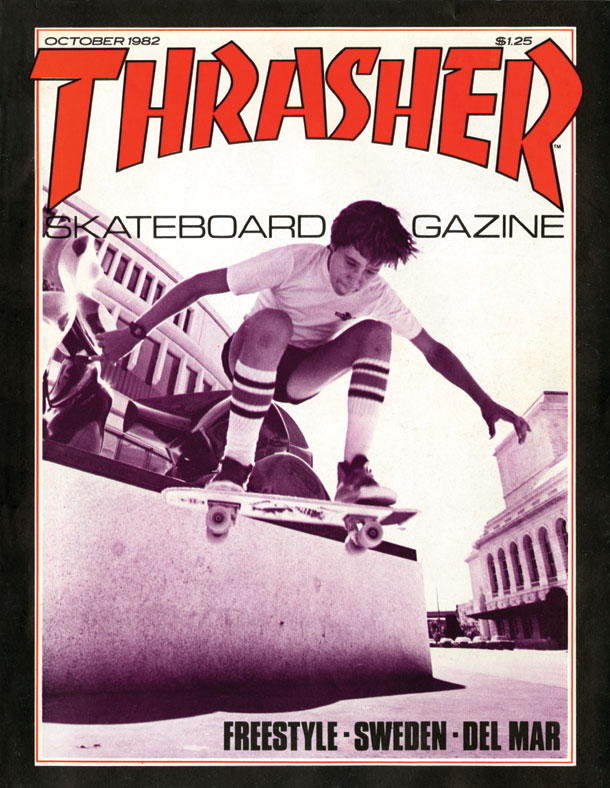

Society’s reluctance combined with skateboarding’s yet unfulfilled adaptability made skateboarding disappear from the public eye once again in the early 1980’s. With no skateparks and most of the city terrain still inaccessible, skateboarders in this time withdrew to homebuilt wooden vertical ramps and flatground freestyle.

The vertical ramp skating developed fast in the 1980’s and soon became spectacular enough to catch the eye of the outside world. The skateboard industry flourished again by the mid 80’s with the big name professional ramp heroes untouchably high up in the air and the flatground freestylers hard at work on their less extravagant techniques down below.

But this easy split of skateboarding with the worshiped ramp professionals and the mocked flatground skaters would become more confused and blurred as the 1990’s approached.

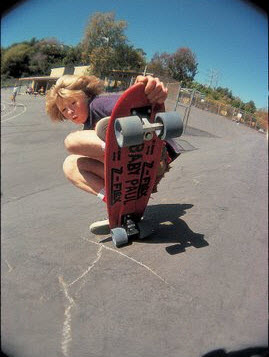

Because, in 1982 professional freestyle skater Rodney Mullen had unknowingly created skateboarding’s most important maneuver – the flatground ollie. The ollie was originally a no-handed aerial turn pioneered on vertical terrain by Alan “Ollie” Gelfand in 1976, but it was when Mullen figured out how to trick his skateboard to pop off the flat ground only using his feet, that the future of skateboarding changed.

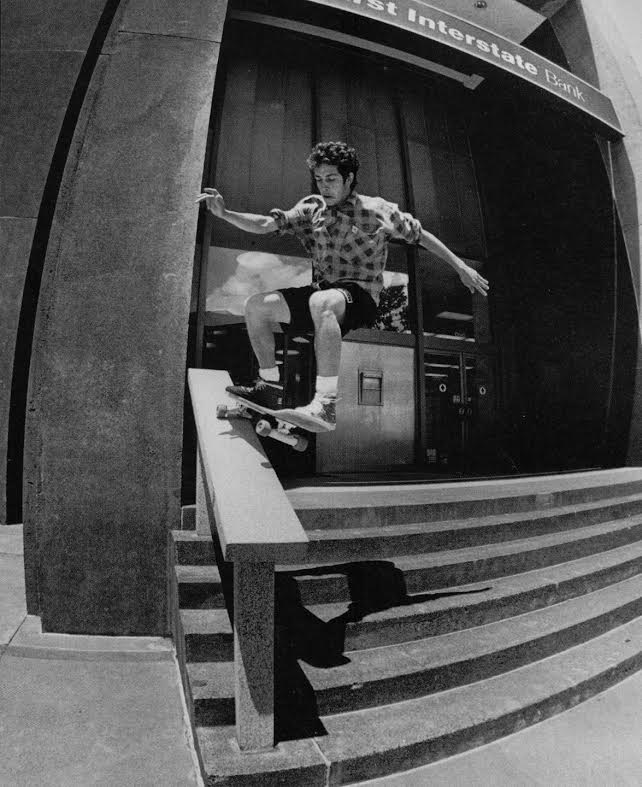

A few young Californian skaters with one foot in ramp skating and one foot in flatground freestyle soon mastered the ollie to a degree where they could mimic popular ramp tricks like aerials and different grinds and slides – right outside their homes – on benches, curbs, walls and embankments! By use of the ollie, the city was being transformed into one great skatepark, limitless and free of charge for anyone willing to achieve the necessary techniques.

The re-claiming of the streets

The street revolution of the late 1980’s is the most important change in skateboarding ever. It was unstoppable and would prove to be as merciless as it was necessary for the survival of skateboarding. Big name professional ramp skaters went from millionaire super stardom to obsolete nothingness overnight. The dominants of the skateboard industry went the same way. Too clumsy to move along with the new times and demands they saw themselves going out of business in an instant, overtaken by new, smart and small companies focusing only on street skaters and the new street skating talents.

The re-claiming of the streets as the natural terrain for skateboarding was truly a revolution of the people with the leaders of it rolling among the common. No longer did skaters need to know someone who owned a ramp or pay to get inside a park, no big pads or helmets were needed either. Skateboarding was back where it once started, where anyone could do it, anyway they liked it, in the streets, and to this day, we have not yet seen the end of its possibilities.

The street revolution and the following reign of street skating was not a passing one. The freedom and low maintenance of street skating has made it the by far most popular way of skating from the 1990’s until today and the easy access of street skating is what makes skateboarding an ever growing phenomenon. Although loads of ramp-oriented parks are built worldwide today, a huge majority of all skateboarders prefer street-oriented terrain and media is still very much focused on the action in the streets.

Since the revolution of street skating, skateboarding has not died, faded or withdrawn like it did multiple times before. Since street, skateboarding has just kept on growing and shows no signs of stopping.

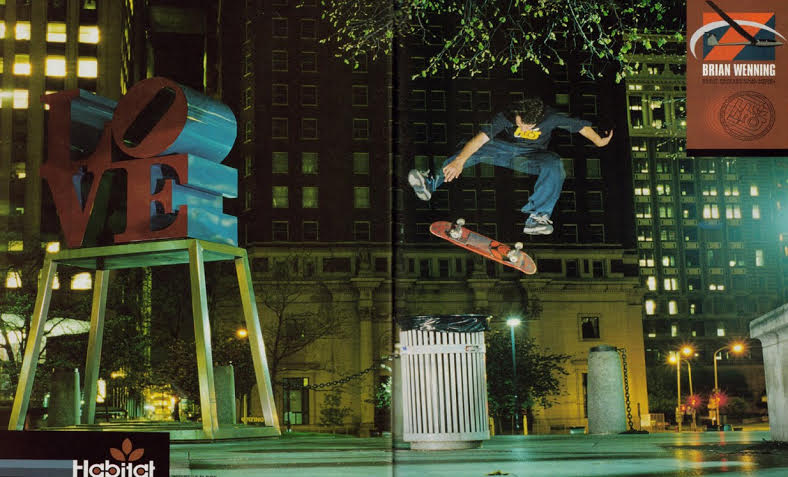

Love Park in Philadelphia

Reign of the street plazas

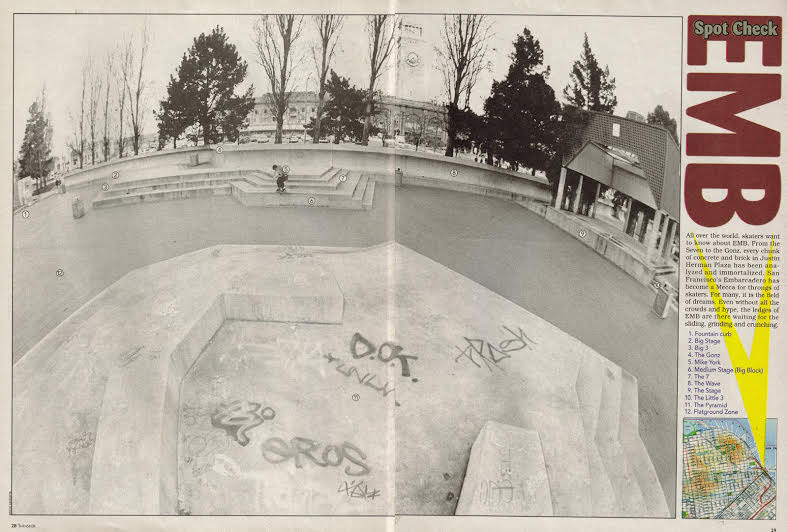

Since the beginning of the 1990’s street skating has evolved around certain “main spots” and their respective local heroes. From Love Park and “Embarcadero” in the U.S., to “MACBA” in Barcelona and “Obsan” in Stockholm (the pond in Observatorielunden) – these spots, or plazas, not in the slightest way designed with skateboarding in mind, have let skateboarders interact and practice in the most natural way. The popularity, fame and importance as places of progression speaks for itself, these kinds of spots are what most skateboarders dream of.

These “main spots” or “plazas” all share a few common traits, which until this day make up for the perfect street spot:

* Vast smooth flat ground

* Square blocks of different heights

Of course, street skating has no real limits terrain-wise and what is possible to skate or not is still being explored – yet the basic plaza terrain seems to hold an everlasting attraction on skateboarders. If a good plaza happens to emerge in a city, the city quickly becomes a skateboarding hub. For example, when skateboarding was allowed outside of Barcelona’s museum of contemporary art –MACBA – Barcelona became the central city for skateboarding worldwide with thousands of skateboard tourists and skateboard immigrants flooding the Catalonian capital, to skate the MACBA plaza and to search the city for more skateable terrain, bringing life, diversity and financial income to every part of the city.

Embarcadero in San Francisco

The street skating conundrum

Unfortunately for skateboarders, not every town has an architecture and city planning like the ones of San Francisco, Los Angeles or Barcelona. Stockholm for example, is a big and in many ways modern city, but still it has not the street skating possibilities that should follow. Architectural traditions and a harsh climate have made the Stockholm street skaters a truly unspoiled lot.

But, one should think that the 10.000.000 Euro spent on concrete skateparks in the Stockholm area in the last 10 years should have made things a bit better? Sadly the answer is no.

The fact is that some 50 percent of what has been built is pure ramp and bowl structures and the other 50 percent is a mix of street and ramp facilities which really is not what most street skaters long for.

In Stockholm Skatepark, the only indoor skatepark in town, the larger of the park’s two buildings is the “ramp room” and the smaller room is the “street room” even though the number of skaters preferring the street room is at least twice the amount of people frequenting the “ramp room”.

When the great 3.300.000 Euro skatepark of Highvalley Skateworld finally opened in 2012 it had no street structures at all.

So how did things end up like this? Well, at Stockholm Skateboard Collective we don’t believe in an evil conspiracy against street skaters. What we believe is that the same old thing is missing that is usually missing when things turn out wrong – knowledge. People working with skatepark design and fundraising for skateparks seem to have missed out on a great deal of the last 25 years of skateboarding. The vast open spaces and simple square blocks that skaters have yearned for since 1990 are still nearly non-existent, which is why Stockholm skateboarders still skate the almost unskateable ledges in the pond in Observatorielunden, when it’s emptied for the winter, rather than skating the brand new concrete skateparks.

The Stockholm Skateboard Collective is standing by, ready to give a helping hand when it comes to skatepark design. Among us we have the designer of the small but very popular plaza-like skateparks in Humlegården, Bredäng and Södertälje.

Stockholm Skateboard Collective is also speaking actively with the city of Stockholm, helping city planners and architects to understand the value of skateboarding in the city and how to make Stockholm a more skate-friendly place. Just drop us a line or give us a call!

PS. Please take note that Stockholm Skateboard Collective is not a bunch of ramp haters. We have the outmost respect for ramp skating and most of us skate ramps on a daily basis. We just want to increase understanding and help see to that the resources set aside for skateboarding are used in a more democratic manner. DS.